The Minimi model made a great impression on the visitors to the Dinosaur Expeditions Centre as it helped to give the Wealden Floodplain diorama some context and scale. During guided tours we explained that it was a work-in-progress and pointed out what we were planning to add to the display.

The centre closed to the public at the end of the main tourism season in November 2013. The priority was to continue work on the Brachiosaur ‘Barn-sized Sauropod skeleton’. Unfortunately the time flew by and we couldn’t mount all of the newly sculpted bones before we had to stop and re-open for the start of the 2014 tourism season. Knowing that once the initial rush of the Spring holidays ebbed away the centre would be quiet for several weeks I had an idea!

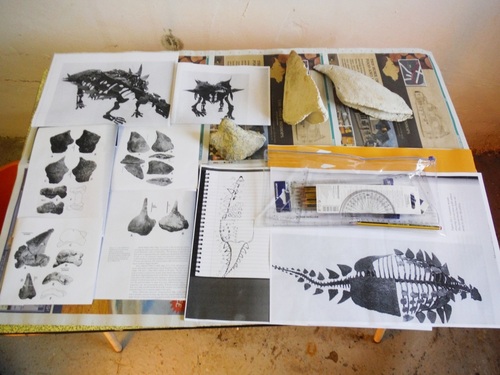

The Minmi needed modifications to change it into a Polacanthus. The head was the wrong shape and lacking in certain details, the body and tail needed spines and the sacral shield over the hips needed enhancing. If the Minmi’s head was removed I could sculpt the modifications required to finish the head, add suitable taxidermy eyes and then reattach it back on to the body before the Summer Holidays. After discussing it with my fellow Directors and assuring them the work would be done with plenty of time to spare the decision was made to saw the head off!

It was a relatively simple to remove the Minmi’s head and drill-out the eyes. I had sourced some milliput from a local art shop and set-up a tray for the Dinosaur head, sculpting tools and materials. I made initial progress, but every time I started sculpting the phone would ring, or visitors would arrive and I would have to stop. I soon realised that not only was the sculpting material not delivering the result I wanted but I wasn’t going to finish the job in time for the Summer Holidays.

One of our visitors, Andre (a professional model sculptor) made recommendations on a different type of sculpting material and I came-up with a new plan. Rather than bulk out the head to match the shape of a different dinosaur, it would be easier to put ‘flesh’ on a cast of the skull. The finished result would much more life-like but it would cost a lot more.

However before going to Plan B, I would have to explain to the other Directors what had gone wrong and that the cost of the job would go up significantly. Fortunately they were very understanding given the circumstances. However it was decided that we would have to wait until the end of the tourism season to ensure we could afford to order a cast of the skull and the professional sculpting material that would form the finished head.

In the meantime there was a headless Minmi / Polacanthus on the diorama, so I improvised by reusing part of the original cardboard packaging and a marker pen to produce a cardboard head.

This provoked a lot of comment by visitors wondering what had happened to the dinosaur’s head? In some ways it became a feature of our guided tours of the centre in 2014 and it certainly engaged children and adults alike with the ‘reveal’ when the cardboard head was removed!

As the 2014 tourism season drew to a close, my attention returned to the forlorn looking dinosaur on the diorama and I resolved to get it finished over the coming winter.